Industrialization & Reform

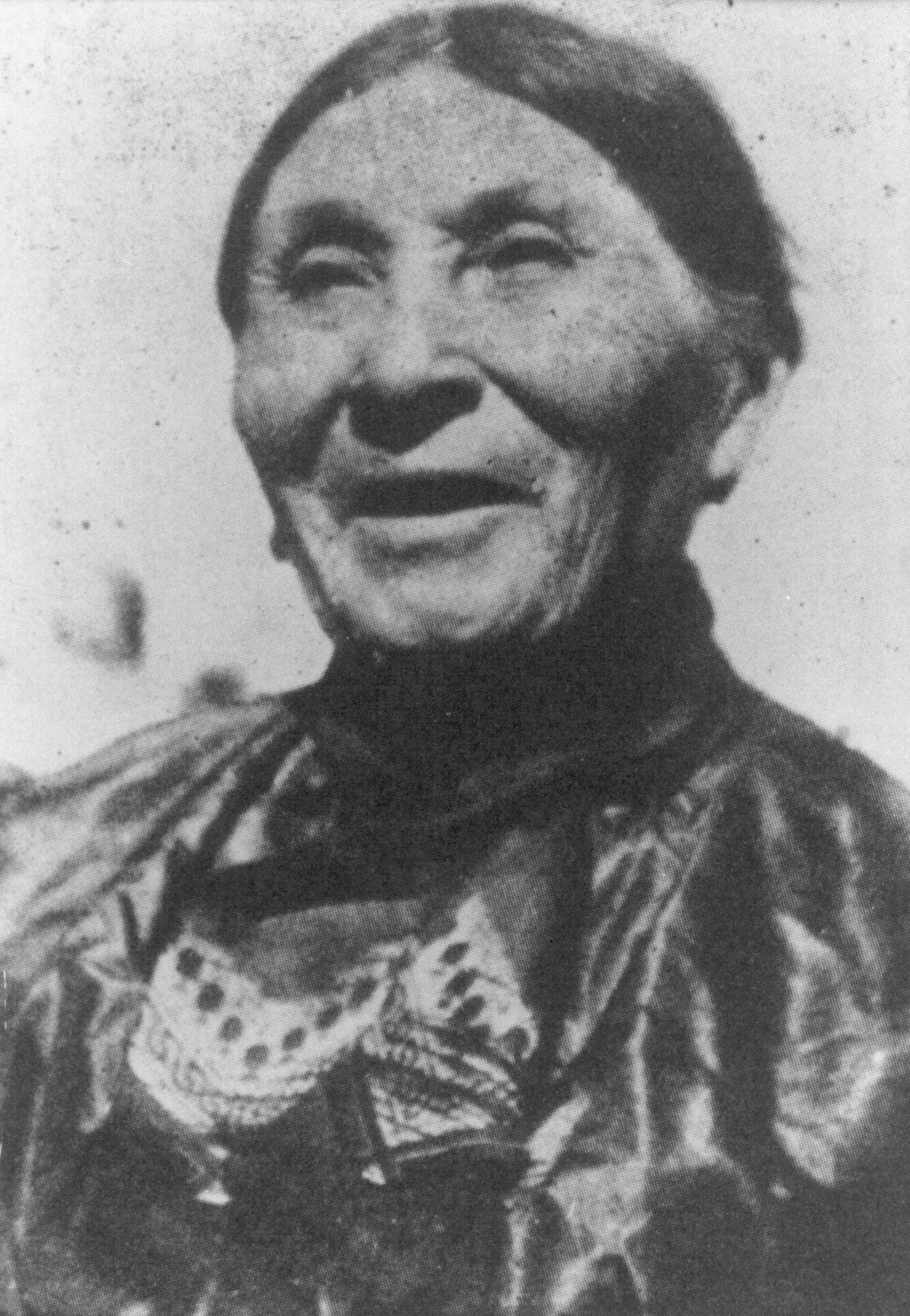

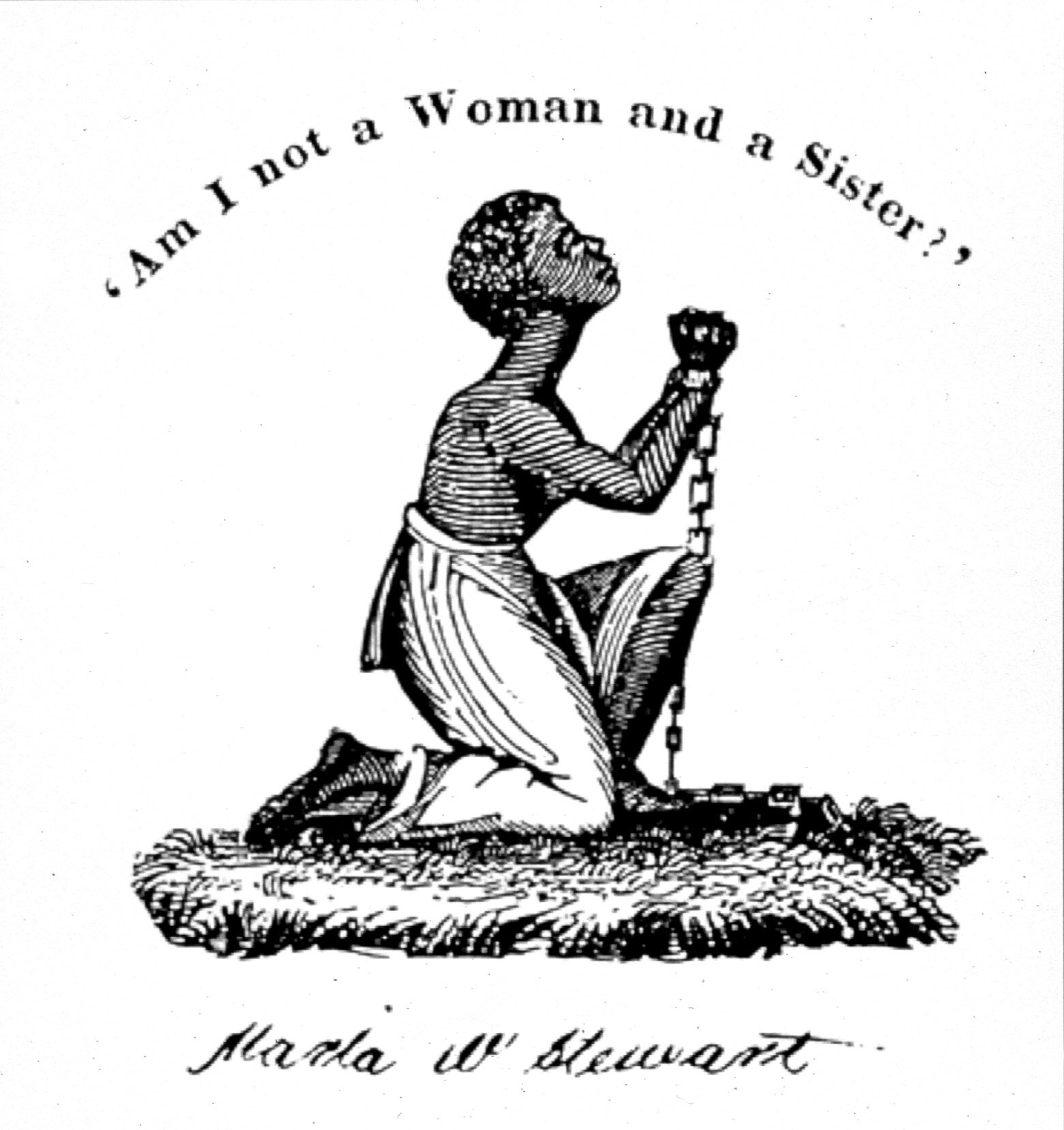

When the Declaration of Independence announced that all men are created equal, the path to citizenship for both blacks and women had begun. Despite not having the right to vote, women had long petitioned governors and legislatures to articulate a family grievance. Activist women presented to the U.S. Congress a large-scale innovative petition on behalf of abolition. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is widely credited with stirring public opinion, especially among women, to anti-slavery sentiments. Helped by women’s efforts, abolitionists eventually secured their goal in the three post-Civil War amendments.

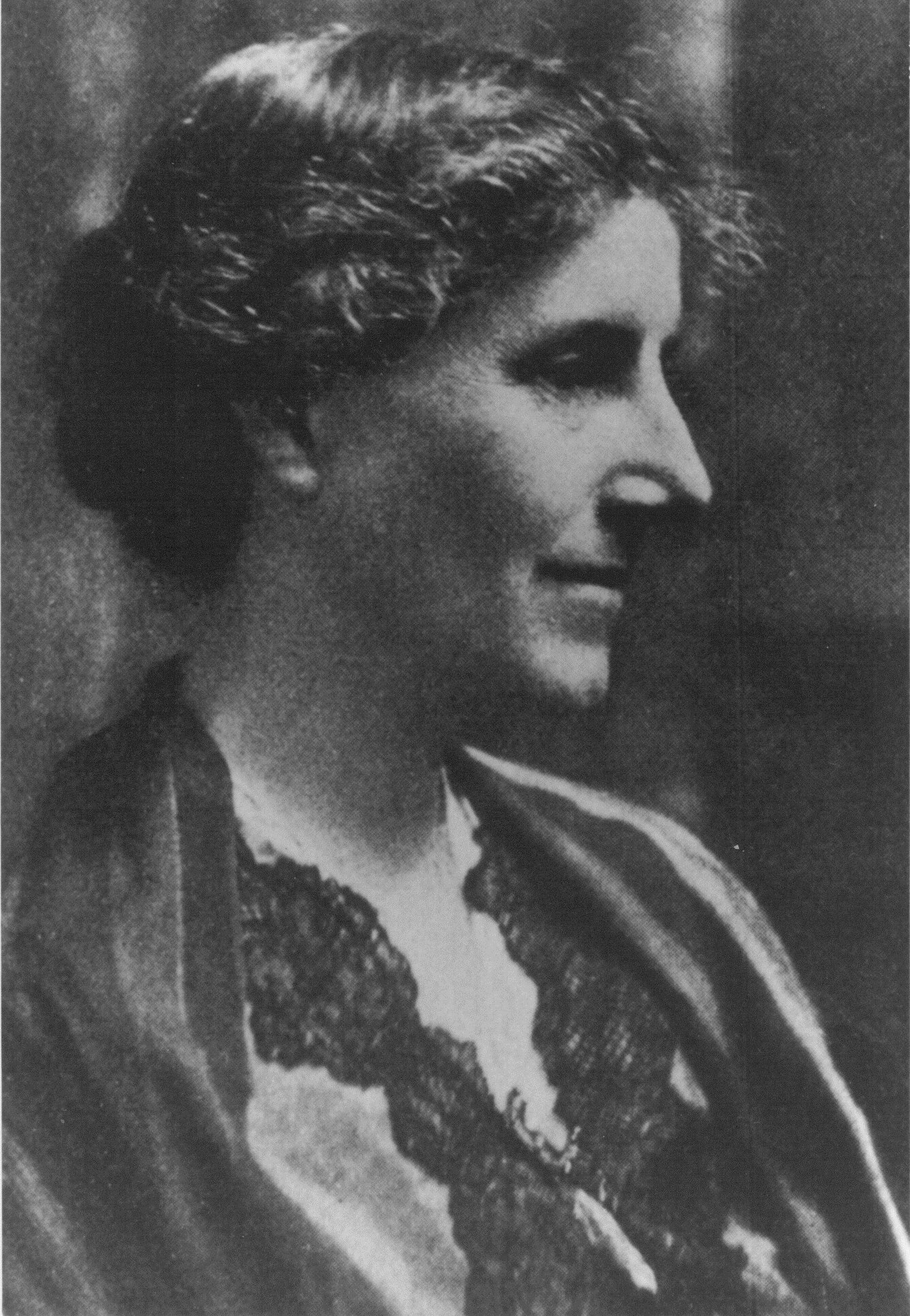

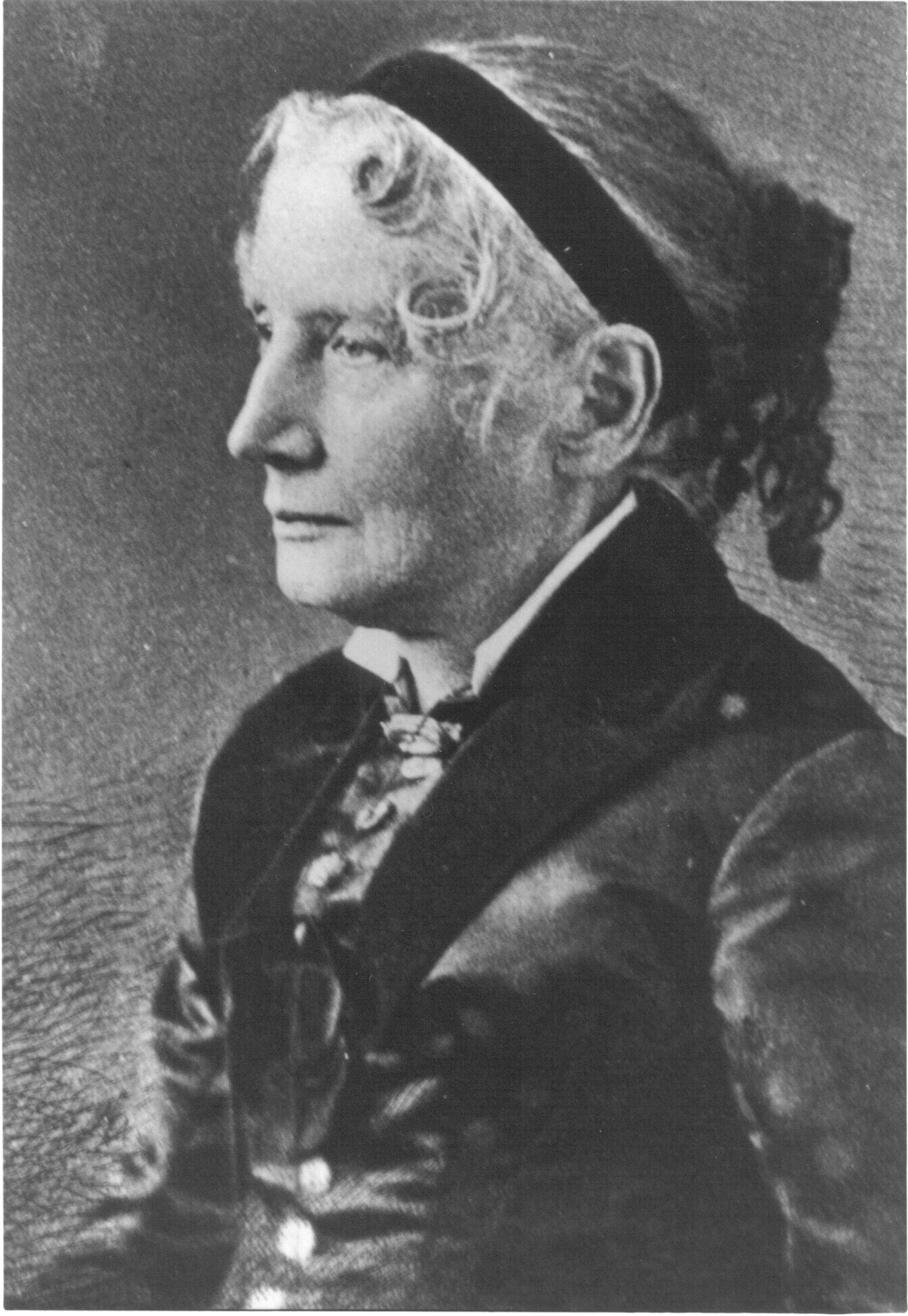

Work in activities such as anti-slavery, temperance and moral reform led some middle-class women to the cause of women’s rights. They challenged the ideal of “separate spheres,” insisting on the same rights to life, liberty, property, and happiness as men. Through Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s lobbying, New York gave women control over their property, wages, and children. In 1848, Stanton and others met in Seneca Falls to discuss the “repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman.” The resulting Declaration of Sentiments asserted that “woman is man’s equal.”

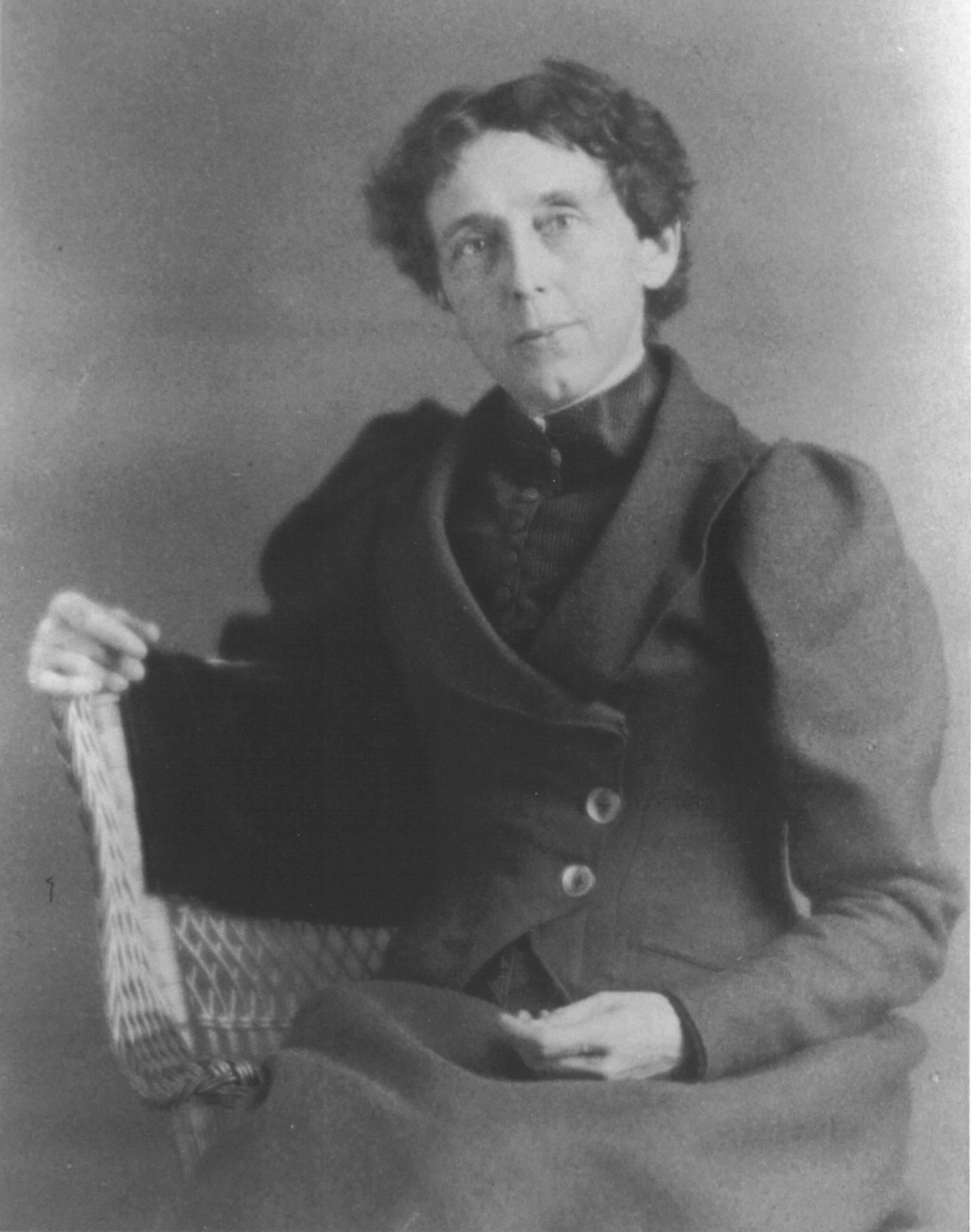

The early industrial economy had changed women’s lives. Textile production shifted from home to factory towns where farm daughters hoped wage labor would open new opportunities. Arrangements seemed ideal, until declining profits caused owners to slash wages to reduce costs. Lowell women walked out in 1836, and later petitioned the legislature to investigate deteriorating conditions. The labor force also changed as more immigrants arrived, delegated to poorly paid factory and domestic work.

In the Progressive Era, some benevolent women were committed to helping working-class women, and their needs received increased publicity after the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire in 1911. Others addressed civic concerns, established settlement houses, worked for protective labor legislation, and tried to ban child labor. Clerical work in offices opened up as a desirable field for women, and some gained greater entry into various professions, including medicine, law, social work, nursing, and teaching.

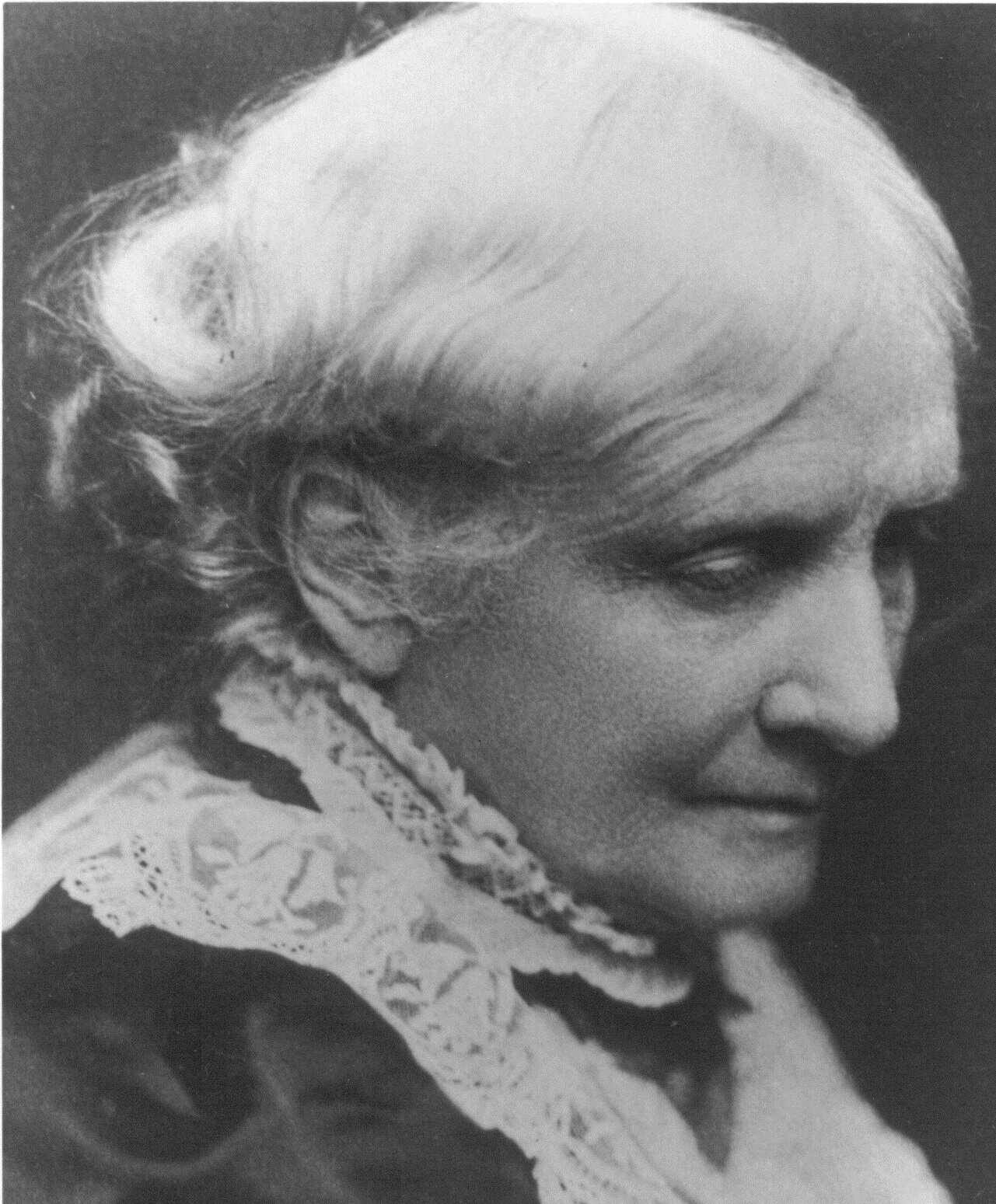

Determined suffragists persisted in their political protests even after World War I broke out in 1914. Finally, seventy-two years after the Seneca Falls convention, employing new tactics and strategies, and a long, hard struggle at the state and national levels, the elusive goal was reached. The 19th amendment, proposed by Congress and ratified by the states in 1920, prohibited restrictions on the right to vote based on sex. It was one of the most successful mass movements in the expansion of political democracy in American history.

An important expression of feminism (calling for change in women’s private lives, not in their public roles) was the campaign in favor of access to birth control. Nurse Margaret Sanger spoke and wrote on its behalf, though her mailings were judged as violating the anti-obscenity Comstock laws. In 1916, after opening the first birth control clinic in the country, she was arrested and sentenced briefly to jail. For forty years she promoted contraception as an alternative to abortion, foreshadowing Planned Parenthood.

Special thanks to Barbara E. Lacey, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of History, St. Joseph's College (Hartford, CT) for preparing these historical summaries.